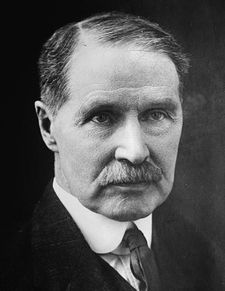

George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

| The Most Honourable The Marquess Curzon of Kedleston KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC |

|

Lord Curzon of Kedleston as Viceroy of India |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office 6 January 1899 – 18 November 1905 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria Edward VII |

| Deputy | The Lord Ampthill |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Elgin |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Minto |

|

Foreign Secretary

|

|

| In office 23 October 1919 – 22 January 1924 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George Andrew Bonar Law Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | Arthur Balfour |

| Succeeded by | Ramsay MacDonald |

|

Leader of the House of Lords

|

|

| In office 3 November 1924 – 20 March 1925 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | The Viscount Haldane |

| Succeeded by | The Marquess of Salisbury |

| In office 10 December 1916 – 22 January 1924 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George Andrew Bonar Law Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Crewe |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Haldane |

|

Lord President of the Council

|

|

| In office 3 November 1924 – 20 March 1925 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | Stanley Baldwin |

| Preceded by | The Lord Parmoor |

| Succeeded by | The Earl of Balfour |

| In office 10 December 1916 – 23 October 1919 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Crewe |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Balfour |

|

President of the Air Board

|

|

| In office 15 May 1916 – 3 January 1917 |

|

| Monarch | George V |

| Prime Minister | H.H. Asquith David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | The Earl of Derby |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Cowdray |

|

|

|

| Born | 11 January 1859 Kedleston, Derbyshire, United Kingdom |

| Died | 20 March 1925 (aged 66) London, United Kingdom |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Curzon (1895-1906) Grace Curzon (1917-1925) |

| Alma mater | Balliol College, Oxford |

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), known as The Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and as The Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman who was Viceroy of India and Foreign Secretary.

Early life

Curzon was the eldest son and second of 11 children of Alfred Curzon, the 4th Baron Scarsdale (1831–1916), Rector of Kedleston in Derbyshire, and his wife Blanche (1837–1875), daughter of Joseph Pocklington Senhouse of Netherhall in Cumberland. He was born at Kedleston Hall, built on the site where his family, who were of Norman ancestry, had lived since the 12th century. His mother, worn out by childbirth, died when George was 16; her husband survived her by 41 years. Neither parent exerted a major influence on Curzon's life. The Baron was an austere and unindulgent father who believed in the long-held family tradition that landowners should stay on their land and not go "roaming about all over the world". He thus had little sympathy for those travels across Asia between 1887 and 1895 which made his son one of the most traveled men who ever sat in a British cabinet. A more decisive presence in Curzon's childhood was that of his brutal governess, Ellen Mary Paraman, whose tyranny in the nursery stimulated his combative qualities and encouraged the obsessional side of his nature. Paraman periodically forced him to parade through the village wearing a conical hat bearing the words liar, sneak, and coward. Curzon later noted, "No children well born and well-placed ever cried so much and so justly."[1]

He was educated at Eton College[2] and Balliol College, Oxford. At Eton he was a favorite of Oscar Browning, an over-intimate relationship that lead to his tutor's dismissal.[3][4] While at Eton, he was a controversial figure who was liked and disliked with equal intensity by large numbers of masters and other boys. This strange talent for both attraction and repulsion stayed with him all his life: few people ever felt neutral about him. At Oxford he was President of the Union and Secretary of the Oxford Canning Club. Although he failed to achieve a first class degree in Greats, he won the Lothian and Arnold Prizes, the latter for an essay on Sir Thomas More (about whom he confessed to having known almost nothing before commencing study, literally delivered as the clocks were chiming midnight on the day of the deadline). He was elected a prize fellow of All Souls College in 1883.

A teenage spinal injury, incurred while riding, left Curzon in lifelong pain, often resulting in insomnia, and required him to wear a metal corset, contributing to an unfortunate impression of stiffness and arrogance. While at Oxford, Curzon was the inspiration for the following Balliol rhyme, a piece of doggerel which stuck with him in later life:

My name is George Nathaniel Curzon,

I am a most superior person.

My cheeks are pink, my hair is sleek,

I dine at Blenheim twice a week.

Early career and Parliament

Curzon became Assistant Private Secretary to Lord Salisbury in 1885, and in 1886 entered Parliament as Member for Southport in south-west Lancashire. His maiden speech, which was chiefly an attack on home rule and Irish nationalism, was regarded in much the same way as his oratory at the Oxford Union: brilliant and eloquent but also presumptuous and rather too self-assured. Subsequent performances in the Commons, often dealing with Ireland or reform of the House of Lords (which he supported), received similar verdicts. He was Under-Secretary of State for India in 1891-1892 and Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in 1895–1898.

In the meantime he had travelled around the world: Russia and Central Asia (1888-9), a long tour of Persia (1889–90), Siam, French Indochina and Korea (1892), and a daring foray into Afghanistan and the Pamirs (1894), and published several books describing central and eastern Asia and related policy issues. A bold and compulsive traveller, fascinated by oriental life and geography, he was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society for his exploration of the source of the Amu Darya (Oxus). Yet the main purpose of his journeys was political: they formed part of a vast and comprehensive project to study the problems of Asia and their implications for British India. At the same time they reinforced his pride in his nation and her imperial mission.

First marriage (1895–1906)

In 1895 he married Mary Victoria Leiter, the daughter of Levi Ziegler Leiter, an American millionaire of German Lutheran origin and co-founder of the Chicago department store Field & Leiter (now Marshall Field). She had a long and nearly fatal illness near the end of summer 1904, from which she never really recovered. Falling ill again in July 1906, she died on the 18th of that month in her husband's arms, at the age of 36.[5] It was the greatest personal loss of his life.

She was buried in the church at Kedleston, where Curzon designed his memorial for her, a Gothic chapel added to the north side of the nave. Although he was neither a devout nor a conventional churchman, Curzon retained a simple religious faith; in later years he sometimes said that he was not afraid of death because it would enable him to join Mary in heaven.

They had three daughters during a firm and happy marriage: Mary Irene, who inherited her father's Barony of Ravensdale and was created a life peer in her own right; Cynthia, who became the first wife of the controversial politician Sir Oswald Mosley; and Alexandra Naldera ("Baba"), who married Edward "Fruity" Metcalfe, the best friend, best man and equerry of Edward VIII. Mosley exercised a strange fascination for the Curzon women: Mary had a brief romance with him before either were married; Baba became his mistress; and Curzon's second wife, Grace, had a long affair with him.

Viceroy of India (1898–1905)

In January 1899 he was appointed Viceroy of India. He was created a Peer of Ireland as Baron Curzon of Kedleston, in the County of Derby,[6] on his appointment. This peerage was created in the Peerage of Ireland (the last so created) so that he would be free, until his father's death, to re-enter the House of Commons on his return to Britain.

Reaching India shortly after the suppression of the frontier risings of 1897–1898, he paid special attention to the independent tribes of the north-west frontier, inaugurated a new province called the North West Frontier Province, and pursued a policy of forceful control mingled with conciliation. The only major armed outbreak on this frontier during the period of his administration was the Mahsud-Waziri campaign of 1901.

In the context of the Great Game between the British and Russian Empires for control of Central Asia, he held deep mistrust of Russian intentions. This led him to encourage British trade in Persia, and he paid a visit to the Persian Gulf in 1903. At the end of that year, he sent a British expedition to Tibet under Francis Younghusband, ostensibly to forestall a Russian advance. After bloody conflicts with Tibet's poorly-armed defenders, the mission penetrated to Lhasa, where a treaty was signed in September 1904. No Russian presence was found in Lhasa.

Within India, Curzon appointed a number of commissions to inquire into education, irrigation, police and other branches of administration, on whose reports legislation was based during his second term of office as viceroy. Reappointed Governor-General in August 1904, he presided over the 1905 partition of Bengal, which roused such bitter opposition among the people of the province that it was later revoked (1911).

He also took an active interest in military matters. In 1901, he founded the Imperial Cadet Corps, or ICC. The ICC was a corps d'elite, designed to give Indian princes and aristocrats military training, after which a few would be given officer commissions in the Indian Army. But these commissions were "special commissions" which did not empower their holders to command any troops. Predictably, this was a major stumbling block to the ICC's success, as it caused much resentment among former cadets. Though the ICC closed in 1914, it was a crucial stage in the drive to Indianise the Indian Army's officer Corps, which was haltingly begun in 1917. Military organisation proved to be the final issue faced by Curzon in India. A difference of opinion with the British military Commander-in-Chief in India, Lord Kitchener, regarding the status of the military member of the council in India, led to a controversy in which Curzon failed to obtain the support of the home government. He resigned in August 1905 and returned to England.

During his tenure, Curzon undertook the restoration of the Taj Mahal, and expressed satisfaction that he had done so.

The Indian famine

A major famine coincided with Curzon's time as viceroy in which 6.1 to 9 million people died.[7] Large parts of India were affected and millions died, and Curzon is nowadays criticised for having done little to fight the famine.[8]. Curzon did, however, implement a variety of measures, including opening up famine reliefs works that fed between 3 and 5 million, reducing taxes and spending vast amounts of money on irrigation works.[9]. However, Curzon did state "any government which imperiled the financial position of India in the interests of prodigal philanthropy would be open to serious criticism; but any government which by indiscriminate alms-giving weakened the fibre and demoralized the self-reliance of the population, would be guilty of a public crime."[7] He also cut back rations that he characterized as "dangerously high" and stiffened relief eligibility by reinstating the Temple tests.[7]

Return to Britain

Arthur Balfour's refusal to recommend an earldom for Curzon in 1905 was repeated by Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, the Liberal Prime Minister, who formed his government the day after Curzon returned to England. In deference to the wishes of the king and the advice of his doctors, Curzon did not stand in the general election of 1906 and thus found himself excluded from public life for the first time in twenty years. It was at this time, the nadir of his career, that he suffered the greatest personal loss of his life. Mary died in 1906 and Curzon devoted himself to private matters, including establishing a new home. In 1907 he was elected Chancellor of Oxford and proved a quite active Chancellor - "[he] threw himself so energetically into the cause of university reform that critics complained he was ruling Oxford like an Indian province."[10]

Representative peer for Ireland (1908)

In 1908, Curzon was elected a representative peer for Ireland, and thus relinquished any idea of returning to the House of Commons. In 1909-1910 he took an active part in opposing the Liberal government's proposal to abolish the legislative veto of the House of Lords, and in 1911 was created Baron Ravensdale, of Ravensdale in the County of Derby, with remainder (in default of heirs male) to his daughters, Viscount Scarsdale, of Scarsdale in the County of Derby, with remainder (in default of heirs male) to the heirs male of his father, and Earl Curzon of Kedleston, in the County of Derby, with the normal remainder, all in the Peerage of the United Kingdom.[11] He served in Lloyd George's War Cabinet as Leader of the House of Lords from December 1916. Despite his continued opposition to votes for women (he had earlier headed the Anti-Suffrage League), the House of Lords voted conclusively in its favour.

Second marriage (1917)

After a long affair with the romance novelist Elinor Glyn, Curzon married in 1917 the former Grace Elvina Hinds, the wealthy Alabama-born widow of Alfred Hubert Duggan; in later years wags joked that despite his political disappointments Curzon still enjoyed "the means of Grace". Glyn, who was staying with Curzon at the time, read of his engagement in the morning newspapers.

His wife had three children from her first marriage. Despite fertility-related operations and several miscarriages, she was not able to give Curzon the son and heir he desperately desired, a fact that eroded their marriage, which ended in separation, though not divorce.

In 1917, Curzon bought Bodiam Castle in East Sussex, a 14th century building that had been gutted during the English Civil War. He restored it extensively, then bequeathed it to the National Trust.[12]

The Great Game

When attempting to understand the foreign policy decisions of many European governments during the late 1800s and the early 1900s it is necessary to place them within the context of the Great Game, and George Curzon is no exception. The Great Game was directly and indirectly responsible for shaping Curzon’s geopolitical strategy when it came to Central Asia, with the protection of Britain’s most valuable colony, India, as the prime goal. While all European powers were viewed as potential threats, Curzon believed Russia to be the most likely challenger to British supremacy in the region from the 1800s through the early 1900s.[13]

When construction of the Transcaspian Railroad along the Silk Road began in 1879, this was perceived by Curzon as an overtly aggressive expansionist project aimed at usurping British control in India. The line starts from the city of Turkmenbashi (on the Caspian Sea), travels southeast along the Karakum Desert, through Ashgabat, continues along the Kopet Dagh Mountains until it reaches Tejen. While Russia maintained the position that the sole purpose of this railroad was to enforce local control, Curzon dedicated an entire chapter in his book Russia in Central Asia to discussing the wider military and commercial ramifications.[14] This railroad connected Russia with the most wealthy and influential cities in Central Asia at the time, including the Persian province of Kosraean.[15] Most apparent to Curzon was that on completion, this railroad would allow the rapid mobilization of Russian forces, adding to the already existing Russian military geographic advantage (a shared border). Russian supplies and troops could be dispersed into the area with considerable ease, bolstering their government’s confidence in fulfilling their imperial ambitions. However powerful the military threat may have been, Curzon also believed there would be damaging commercial consequences, in an increasing exchange of goods between the Russia and the Central Asia region would naturally generate greater economic interdependence.[16]

Curzon later argued for an exclusive British presence in the Persian Gulf, a policy originally proposed by British politician John Malcolm. Indeed the British government was engaged in making agreements with local sheikhs/tribal leaders along the Persian Gulf coast to this end. Curzon was eventually successful in convincing his government to establish Britain as the unofficial protectorate of Kuwait (with the Anglo-Kuwaiti Agreement of 1899) and made the Lansdowne Declaration in 1903.[17] This stated that the British would counter any other European power's attempt to establish a military presence in the Gulf.[18] Only four years later this position was abandoned with the Anglo-Russian Agreement which declared the Persian Gulf a neutral zone. This 1907 agreement was approved by the British government after realizing the high economic cost of defending India from Russian advances.[19]

In 1918, during WWI as Britain’s influence in Iraq was growing, Curzon attempted to convince the Indian government to reconsider his Iranian buffer scheme, which entailed having Iran act as a physical bulwark against Russian territorial advances.[20] He believed that helping to prop-up the Iranian government would make the country politically dependent on the Indian government, affording India a subservient and stable ally. Aid to Iran was to be given through economic incentives and military support, all of which would originate from Great Britain, with the India colony serving as the sole intermediate broker. However, the plan was rejected. The British government's view remained that Russia had the geographical advantage and that the defensive benefits would not justify the high economic cost.[21]

Foreign Secretary (1919–1924)

Appointed Foreign Secretary in October 1919, Curzon gave his name to his line that became the British government's proposed Soviet-Polish boundary, the Curzon Line of December 1919. Although during the subsequent Russo-Polish War Poland conquered ground in the east, Poland was shifted westwards after the Second World War, leaving the Curzon Line approximately the border between Poland and its eastern neighbours today.

Curzon did not have Lloyd George's support. The Prime Minister thought him overly pompous and self-important, and it was said that he used him as if he were using a Rolls-Royce to deliver a parcel to the station; Lloyd George said much later that Churchill treated his Ministers in a way that Lloyd George would never have treated his: "They were all men of substance — well, except Curzon." [22] Curzon nevertheless helped in several Middle Eastern problems: he negotiated Egyptian independence (granted in 1922) and divided the British Mandate of Palestine, creating the Kingdom of Jordan for Faisal's brother, which may also have delayed the problems there.

Curzon was largely responsible for the first Armistice Day ceremonies on 11 November 1919. These included the plaster Cenotaph, designed by the noted British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, for the Allied Victory parade in London, and it was so successful that it was reproduced in stone, and still stands. In 1921 he was created Earl of Kedleston, in the County of Derby, and Marquess Curzon of Kedleston.[23]

Unlike many leading Conservative members of Lloyd George's Coalition Cabinet, Curzon ceased to support Lloyd George over the Chanak Crisis and had just resigned when Conservative backbenchers voted at the Carlton Club meeting to end the Coalition in October 1922. Curzon was thus able to remain Foreign Secretary when Andrew Bonar Law formed a purely Conservative ministry. In 1922-3 Curzon had to negotiate with France after French troops occupied the Ruhr to enforce the payment of German reparations; he described the French Prime Minister (and former President) Raymond Poincaré as a "horrid little man".

On Andrew Bonar Law's retirement as Prime Minister in May 1923, Curzon was passed over for the job in favour of Stanley Baldwin, despite having written Bonar Law a lengthy letter earlier in the year complaining of rumours that he was to retire in Baldwin's favour, and listing the reasons why he should have the top job. Many reasons are often cited for this decision - taken on the private advice of leading members of the party including former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour - but amongst the most prominent are that Curzon's character was objectionable, that it was felt to be inappropriate for the Prime Minister to be a member of the House of Lords when Labour, who had few peers, had by then become the main opposition party in the Commons (though this did not prevent Lord Halifax being considered for the premiership in 1940, possibly with a special act to allow him to sit in the House of Commons; in 1963 Lords Home and Hailsham were only able to be candidates owing to recent legislation permitting them to disclaim their peerages) and that in a democratic age it would be dangerous for a party to be led by a rich aristocrat. A letter purporting to detail the opinions of Bonar Law but in actuality written by Baldwin sympathisers was delivered to the King's Private Secretary Lord Stamfordham, though it is unclear how much impact this had in the final outcome. Balfour advised the monarch that it was essential for the prime minister to be in the House of Commons, but in private admitted that he was prejudiced against Curzon. George V, who shared this prejudice, was grateful for the advice and authorised Stamfordham to summon the foreign secretary to London and inform him that Baldwin would be chosen. Curzon travelled by train assuming he was to be appointed Prime Minister, and is said to have burst into tears when told the truth. He later described Baldwin as "a man of the utmost insignificance", although he served under Baldwin and proposed him for leadership of the Conservative Party.

Curzon remained Foreign Secretary under Baldwin until the government fell in January 1924. When Baldwin formed a new government in November 1924 he appointed Curzon Lord President of the Council. Curzon held this post until the following March. That month, while staying the night at Cambridge, he suffered a severe haemorrhage of the bladder. He was taken to London the next day, and on 9 March an operation was performed. But he knew it was the end, that the suffering and overburdened body, which he had pushed so hard for so long, was giving up. He died in London on 20 March 1925 at the age of 66. His coffin, made from the same tree at Kedleston that had encased Mary, was taken to Westminster Abbey and from there to his ancestral home, where he was interred beside Mary in the family vault on 26 March. Upon his death the Barony, Earldom and Marquessate of Curzon of Kedleston and the Earldom of Kedleston became extinct, whilst the Viscountcy and Barony of Scarsdale were inherited by a nephew. The Barony of Ravensdale was inherited by his eldest daughter Mary and is today held by Cynthia's son Nicholas Mosley.

Relationship with domestic politicians

While his vast knowledge of Central Asia earned him considerable respect from his fellow ministers, his arrogant nature and often brutally blunt criticism caused considerable friction between himself and his peers. As a staunch believer that his position as foreign secretary should be non-partisan, he would objectively present all the information on a subject to the cabinet, as if placing faith in his fellow ministers to reach the appropriate policy decision. Conversely, Curzon viewed any political critiques or criticism of his office or policy suggestions, as personal attacks which would prompt aggressive responses from him.[24] It has been recently suggested by scholars that this fierce defense of his office was born out of political insecurity of the Foreign Office as a whole. During the 1920s in Britain, foreign policy was mainly reactive and dominated by the Prime Minister, often leaving the Foreign Office to be a passive participant in foreign policy decision making.[25] Adding to the uncertain fate of the Foreign Office was the introduction of new actors to the political discourse such as, the creation of the Colonial Secretary, the position of Cabinet Secretariat, an official who was responsible for all communications between the British government, and the other new actor, the League of Nations.[26]

His most unhappy years were believed to have been spent under Lloyd George, based on the multiple drafts of resignation letters written at this time found upon Curzon’s death. The professional animosity between the two can be traced back to the 1911 Parliament Crisis, however there were also more personal reasons for their hostile relationship. Lloyd George greatly disliked Curzon for the aristocratic nature he exuded. Despite their antagonistic relationship, when it came to the content of governmental policy the two were often in agreement.[27] Lloyd George recognized the wealth of knowledge Curzon possessed as being crucial to the success of his coalition government and so he served as both his biggest critic and simultaneously as his largest supporter.[28] Likewise, Curzon was grateful for the latitude Lloyd George bestowed upon him when it came to handling affairs in the Middle East. Curzon’s unhappiness with his superiors was not solely reserved for Lloyd George. In fact he was also unhappy with Lloyd George’s successor, Bonar Law, who became Prime Minister in November 1922. Bonar Law’s foreign policy position was based on a platform of “retrenchment and withdrawal”, which contrasted sharply with Curzon’s expansive ambitions.[29] Despite Curzon’s seemingly consistent discontent with his domestic political peers, he provided invaluable insight on the Middle East and was instrumental in shaping British foreign policy in that region.

Titles

On his appointment as Viceroy of India in 1898 he was created Baron Curzon of Kedleston, in the County of Derby. This title was created in the Peerage of Ireland to enable him to potentially return to the House of Commons, as Irish peers did not have an automatic right to sit in the House of Lords.

In 1911 he was created Earl Curzon of Kedleston, Viscount Scarsdale, and Baron Ravensdale. All of these titles were in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and thus precluded Curzon's return to the House of Commons, but conferred upon him the right to sit in the House of Lords.

Upon his father's death in 1916, he also became 5th Baron Scarsdale, in the Peerage of Great Britain. The title had been created in 1761.

In the 1921 Birthday Honours he was created Marquess Curzon of Kedleston and Earl of Kedleston.[30]

Styles

- 1859–1886: The Hon. George Nathaniel Curzon

- 1886–1898: The Hon. George Nathaniel Curzon, MP

- 1898–1899: The Rt Hon. The Lord Curzon of Kedleston

- 1899–1901: His Excellency The Rt Hon. The Lord Curzon of Kedleston, GCSI, GCIE

- 1901–1905: His Excellency The Rt Hon. The Lord Curzon of Kedleston, GCSI, GCIE, PC

- 1905–1911: The Rt Hon. The Lord Curzon of Kedleston, GCSI, GCIE, PC

- 1911–1916: The Rt Hon. The Earl Curzon of Kedleston, GCSI, GCIE, PC

- 1916–1921: The Rt Hon. The Earl Curzon of Kedleston, KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC

- 1921–1925: The Most Hon. The Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC

Assessment

Few statesmen have experienced such changes in fortune in both their public and their personal lives. Curzon's career was an almost unparalleled blend of triumph and disappointment. Although he was the last and in many ways the greatest of Victorian viceroys, his term of office ended in resignation, empty of recognition and devoid of reward. After ten years in the political wilderness, he returned to government; yet, in spite of his knowledge and experience of the world, he was unable to assert himself fully as foreign secretary until the last weeks of Lloyd George's premiership. Finally, after he had restored his reputation at Lausanne, his ultimate ambition was thwarted by George V.

There was a feeling after his death that Curzon had failed to reach the heights that his youthful talents had seemed destined to reach. This sense of opportunities missed was summed up by Winston Churchill in his book Great Contemporaries (1937):

The morning had been golden; the noontide was bronze; and the evening lead. But all were polished till it shone after its fashion.

The first leader of independent India, Nehru, paid Curzon a surprising tribute, presumably referring to the fact that Curzon as Viceroy exhibited real love and knowledge of Indian culture: After every other Viceroy has been forgotten, Curzon will be remembered because he restored all that was beautiful in India.

It is believed that his name was given to a new school built in 1938 - Curzon Crescent Nursery School, Willesden, Middlesex, due to the area's links with All Souls.

Curzon Hall, the base of the science department of the University of Dhaka has been named after him. Lord Curzon himself inaugurated the building in 1904.

Analysis of Persia and the Persian Question

This work, written in 1892, has been considered Curzon’s magnum opus and the culmination of both Curzon’s travel experiences in the region (September 1889-January1890) as well as scholarship gathered after he returned from Persia. It can be seen as a sequel to his earlier book Russia in Central Asia.[31] The impetus for his trip to Persia was his commission by The Times to write several articles on the current Persian political environment. However while there Curzon had decided that his ultimate personal goal would be a book on the country as whole.[32] This two volume work covers a wide array of topics, such as Persia's history and its governmental structure, providing the reader with as complete an understanding of Persia as possible from a foreigner’s perspective. The text is enhanced with graphics, maps and pictures (some taken by Curzon himself). The comprehensiveness with which Curzon covered Persia was made possible by two invaluable sources, General Albert Houtum Schindler and the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), both of which helped him gain access to material to which as a foreigner he would not have been access.[33] General Schindler (a naturalized British subject and Inspector of Persian Telegraphs) provided Curzon with information regarding Persia’s geography and resources, as well as serving as an unofficial editor. The map which accompanied the volumes was the product of RGS, but was later pointed out as inaccurate (according to British officials) as it depicted the islands near the Straits of Hormuz (Sirri, Abu Musa, and the Tunbs) as belonging to the Persians.[34]

The author's political agenda is apparent. Long before becoming Foreign Secretary, Curzon was appalled by his government’s apathy towards Persia as a valuable asset, especially when it had the potential to serve as a defensive buffer to India from Russian encroachment.[35] Even years after Persia entered British foreign policy and geostrategic discourse, Curzon would lament that “Persia has alternatively advanced and receded in the estimation of British statesmen, occupying now a position of extravagant prominence, anon one of unmerited obscurity.”[36] So it can be inferred that the author's intended audience was what he saw as an ignorant British government, and his hope the book would result in a more informed consideration of Persia as a valuable ally/pawn in imperial policies in Central Asia.

Notes

- ↑ Empire, Niall Ferguson

- ↑ Eton, the Raj and modern India; By Alastair Lawson; 9 March 2005; BBC News.

- ↑ ". . . Oscar Browning (1837-1923), who had been sacked from Eton in September 1875 under suspicion of paederasty, partly because of his involvement with young George Nathaniel Curzon" in Michael Kaylor, Secreted Desires 2006 p.98

- ↑ "His intimate, indiscreet friendship with a boy in another boarding-house, G. N. Curzon [...] provoked a crisis with [Headmaster] Hornby [….] Amid national controversy he was dismissed in 1875 on the pretext of administrative inefficiency but actually because his influence was thought to be sexually contagious" in Richard Davenport-Hines, Oscar Browning DNB

- ↑ Maximilian Genealogy Master Database, Mary Victoria LEITER, 2000

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 27016, p. 6140, 21 October 1898.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Davis, Mike. Late Victorian Holocausts. 1. Verso, 2000. ISBN 1-85984-739-0 pg 158

- ↑ Mike Davis (scholar): Late Victorian Holocausts

- ↑ David Gilmour's Curzon and Ruling Caste. In Curzon he writes that 3.5 million were on famine relief, in Ruling Caste he writes it was over five million.

- ↑ Oxford DNB

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 28547, p. 7951, 3 November 1911.

- ↑ Channel 4 history microsites: Bodiam Castle

- ↑ Curzon, George N. Russia in Central Asia. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1967, 314.

- ↑ Ibid, 272.

- ↑ Wright, Denis. “Curzon and Persia.” The Geographical Journal. 153.3 (November 1987): 343.

- ↑ Curzon, George N. Russia in Central Asia. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1967, 277.

- ↑ Yapp, M.A., “British Perceptions of the Russian Threat to India.” Modern Asian Studies 21.4 (1987): 655.

- ↑ Ibid, 655.

- ↑ Ibid, 664.

- ↑ Ibid, 654.

- ↑ Ibid, 653.

- ↑ Michael Foot: Aneurin Bevan

- ↑ London Gazette: no. 32376, p. 5243, 1 July 1921.

- ↑ Bennett, G.H. "Lloyd George, Curzon and the Control of British Foreign Policy 1919-22."Australian Journal of Politics & History 45.4 (1999): 472.

- ↑ Sharp, Alan "Adapting to a New World? British Foreign Policy in the 1920s." Contemporary British History 18.3 (2004): 76.

- ↑ Bennett, G.H. "Lloyd George, Curzon and the Control of British Foreign Policy 1919-22."Australian Journal of Politics & History 45.4 (1999): 473.

- ↑ Johnson, Gaynor "Preparing for Office: Lord Curzon as Acting Foreign Secretary, January- October 1919." Contemporary British History 18.3 (2004): 56.

- ↑ Bennett, G.H. "Lloyd George, Curzon and the Control of British Foreign Policy 1919-22." Australian Journal of Politics & History 45.4 (1999): 479.

- ↑ Ibid, 477.

- ↑ London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 32346, p. 4529, 4 June 1921.

- ↑ Wright, Denis. "Curzon and Persia." The Geographical Journal. 153.3 (November 1987):346.

- ↑ Ibid, 346.

- ↑ Ibid, 346.

- ↑ Ibid, 347.

- ↑ Brockway, Thomas P. “Britain and the Persian Bubble, 1888-1892.” The Journal of Modern History. 13.1(March 1941):46.

- ↑ Curzon, George N. Persia and the Persian Question (Volume 1). New York: Barnes & Noble, 1966,605.

Bibliography

George Nathaniel Curzon's writings

- Curzon, Russia in Central Asia in 1889 and the Anglo-Russian Question, (1889) Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., London (reprinted Cass, 1967), Adamant Media Corporation ISBN 978-1-4021-7543-5 (February 27, 2001) Reprint (Paperback) Details

- Curzon, Persia and the Persian Question (1892) Longmans, Green, and Co., London and New York.; facsimile reprint:

- Curzon, Problems of the Far East (1894; new ed., 1896) George Nathaniel Curzon Problems of the Far East. Japan -Korea - China, reprint, ISBN 1-4021-8480-8, ISBN 978-1-4021-8480-2 (December 25, 2000) Adamant Media Corporation (Paperback)Abstract

- Curzon, "The Pamirs and the Source of the Oxus", 1897, The Royal Geographical Society. Geographical Journal 8 (1896): 97-119, 239-63. A thorough study of the region’s history and people and of the British - Russian conflict of interest in Turkestan based on Curzon’s travels there in 1894. Reprint (paperback): Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 978-1-4021-5983-1 (April 22, 2002) Abstract. Unabridged reprint (2005): Elbiron Classics, Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-5983-8 (pbk); ISBN 1-4021-3090-2 (hardcover).

- Curzon, The Romanes Lecture 1907, "FRONTIERS", By the Right Honorable Lord Curzon of Kedleston G.C.S.I., G.C.I.E., PC, D.C.L., LL.D., F.R.S., All Souls College, Chancellor of the University, Delivered in the Sheldonian Theater, Oxford, November 2, 1907 full text.

- Curzon, "Tales of Travel" First published by Hodder & Stoughton 1923, (Century Classic Ser.) London, Century. 1989, Facsimile Reprint. ISBN 0-7126-2245-4, Soft Cover. Reprint with Foreword by Lady Alexandra Metcalfe, Introduction by Peter King. A selection of Curzon's travel writing including essays on Egypt Afghanistan Persia Iran India Iraq Waterfalls etc. 12 + 344p., Includes the future viceroy’s escapade into Afghanistan to meet the “Iron Emir”, Abdu Rahman Khan, in 1894.

- Curzon, "Travels with a Superior Person", London, Sidgwick & Jackson. 1985, Reprint. ISBN 978-0-283-99294-0, Hardcover,Details A selection from Lord Curzon's travel books between 1889 and 1926, "The quintessence of late Victorian travel writing and a delight for modern readers " Illustrated with 90 contemporary photographs most of them from Curzon's own collection. Includes "Greece in the Eighties" pp. 78–84, " Edited by Peter King. Introduced by Elizabeth Longford. 191p. illus. maps on endpapers.

Secondary sources

- Bennet, G. H. (1995). British Foreign Policy During the Curzon Period, 1919–1924. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-12650-6.

- Carrington, Michael. A PhD thesis, "Empire and authority: Curzon, collisions, character and the Raj, 1899–1905.", discusses a number of interesting issues raised during Curzon's Viceroyalty, (Available through British Library).

- Goudie A. S. (1980). "George Nathaniel Curzon: Superior Geographer", The Geographical Journal, 146, 2 (1980): 203–209, doi:10.2307/632861 Abstract

- Gilmour, David (2003). Curzon: Imperial Statesman. Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-374-13356-5.

- Katouzian, Homa. "The Campaign Against the Anglo-Iranian Agreement of 1919." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 25 (1) (1998): 5–46.

- Nicolson, Harold George (1934). Curzon: The Last Phase, 1919–1925: A Study in Post-war Diplomacy. London: Constable. ASIN B0006AMLTW

- Ronaldshay, Earl of (1927). The life of Lord Curzon. Vol. 1-2. (London)

- Ross, Christopher N. B. "Lord Curzon and E. G. Browne Confront the 'Persian Question'", Historical Journal, 52, 2 (2009): 385–411, doi:10.1017/S0018246X09007511

- Wright, Denis. "Curzon and Persia." The Geographical Journal 153 (3) (1987): 343–350.

References

- Mosley, Leonard Oswald. The glorious fault: The life of Lord Curzon

- Nicolson, Harold. Curzon: the last phase

- Gilmour, David (2003). Curzon - Imperial Statesman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux / John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5547-7. http://www.holtzbrinckpublishers.com/academic/Book/BookDisplay.asp?BookKey=817057. Retrieved 2006-05-25.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Analysis of George Curzon as Viceroy

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by George Curzon

- Problems of the Far East: Japan - Korea - China by George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston at archive.org

- Modern parliamentary eloquence; the Rede lecture, delivered before the University of Cambridge, November 6, 1913 by George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston at archive.org

- Russia In Central Asia In 1889 by George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston at archive.org

- War poems and other translations by George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston at archive.org

- Archival material relating to George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston listed at the UK National Register of Archives

- George Nathaniel CURZON was born 11 Jan 1859. He died 20 Mar 1925. George married Mary Victoria LEITER on 22 Apr 1895

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Augustus Pilkington |

Member of Parliament for Southport 1886–1898 |

Succeeded by Sir Herbert Naylor-Leyland, Bt |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Sir John Eldon Gorst |

Under-Secretary of State for India 1891–1892 |

Succeeded by George William Erskine Russell |

| Preceded by Sir Edward Grey, Bt |

Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs 1895–1898 |

Succeeded by Hon. St John Brodrick |

| Preceded by The Earl of Derby as Chairman of the Joint War Air Committee |

President of the Air Board 1916–1917 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Cowdray |

| Preceded by The Marquess of Crewe |

Lord Privy Seal 1915–1916 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Crawford |

| Preceded by The Marquess of Crewe |

Leader of the House of Lords 1916–1924 |

Succeeded by The Viscount Haldane |

| Lord President of the Council 1916–1919 |

Succeeded by Arthur James Balfour |

|

| Preceded by Arthur James Balfour |

Foreign Secretary 1919–1924 |

Succeeded by Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by The Lord Parmoor |

Lord President of the Council 1924–1925 |

Succeeded by Arthur James Balfour |

| Preceded by The Viscount Haldane |

Leader of the House of Lords 1924–1925 |

Succeeded by The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

| Government offices | ||

| Preceded by The Earl of Elgin |

Viceroy of India 1899–1905 |

Succeeded by The Earl of Minto |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by The Marquess of Lansdowne |

Leader of the Conservative Party in the House of Lords 1916–1925 |

Succeeded by The 4th Marquess of Salisbury |

| Preceded by Andrew Bonar Law |

Leader of the British Conservative Party with Austen Chamberlain 1921–1922 |

Succeeded by Andrew Bonar Law |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury |

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports 1904–1905 |

Succeeded by HRH The Prince of Wales |

| Academic offices | ||

| Preceded by Viscount Goschen |

Chancellor of the University of Oxford 1907–1925 |

Succeeded by Viscount Cave |

| Preceded by H. H. Asquith |

Rector of the University of Glasgow 1908—1911 |

Succeeded by Augustine Birrell |

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

| New creation | Marquess Curzon of Kedleston 1921–1925 |

Extinct |

| New creation | Earl Curzon of Kedleston 1911–1925 |

|

| Viscount Scarsdale 1911–1925 |

Succeeded by Richard Curzon |

|

| Baron Ravensdale 1911–1925 |

Succeeded by Mary Irene Curzon |

|

| Peerage of Great Britain | ||

| Preceded by Alfred Curzon |

Baron Scarsdale 1916–1925 |

Succeeded by Richard Curzon |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| New creation | Baron Curzon of Kedleston 1898–1925 |

Extinct |

| Preceded by The Lord Kilmaine |

Representative peer for Ireland 1908–1925 |

Office lapsed |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)